Beyond Borders, Beyond Paychecks: Unraveling Employee Motivation in Hungary vs. Neighbors

Andras Rusznyak

4/17/202515 min read

Ha magyarul szeretnéd olvasni a cikket, kattints ide

Introduction

Motivation is the invisible engine driving workplace productivity and engagement. Yet, what fuels that engine can differ widely across countries and cultures. In Central Europe, Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Austria share historical ties but nurture distinct workplace cultures. This article compares employee motivation across these nations, with a spotlight on Hungary’s unique profile. We base our analysis on recent research findings to assist experienced HR practitioners in designing effective, localized engagement strategies. By examining factors like financial incentives, meaningful work, supportive leadership, and trust, and looking at gender, generational, and job-level differences, we paint a comprehensive picture of motivation in each context. Engaging visuals (e.g., charts and tables) help distill these comparisons, offering quick takeaways for HR decision-making. Let’s journey beyond borders to discover what truly motivates employees in these four countries.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

This article is intended to be an informative piece, based on various research papers and studies listed under the Sources section. These studies were conducted at different times and each had their own limitations. We did not carry out field research, surveys or interviews, nor did we validate the findings of the mentioned studies under current conditions. It may not be scientifically appropriate to compare the findings of these studies, given their different scopes, but we felt that it might be interesting to share their perspective nonetheless.

We utilized generative AI in the making of this article.

Hungarian workers emerge as strongly people-oriented in their motivation preferences. A 2017 comparative study by Hitka et al. revealed a surprising insight: among 30 factors surveyed, Hungarian employees rated “mutual relationships” (like a good team and workplace atmosphere) as top motivators (2). This emphasis on social needs even outweighed financial factors – a notable divergence from Slovak respondents, who ranked financial rewards highest. Hungarian respondents also placed high importance on career-related factors (e.g., career advancement, personal growth), suggesting a dual focus on interpersonal connection and self-development.

Research in Hungary underscores the significance of meaningful work and supportive management. In a large 2022 study, Csordás et al. validated the Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI) among 2,498 Hungarian employees (3). They found that meaningful work correlates with higher organizational commitment and less absenteeism. This aligns with global trends but offers local validation that Hungarian employees thrive when they find purpose in their roles. As one might expect, leadership quality significantly impacts motivation in Hungary. Pirohov-Tóth (2019) highlights that managerial efforts in sustaining employee contentment are pivotal for performance, reinforcing Vroom’s theory that performance = ability × motivation (4). In Hungarian financial institutions studied, managers who actively cultivate motivation (through recognition, growth opportunities, etc.) see a direct payoff in organizational success.

Trust and engagement also interlink in Hungary’s diverse workforce. With globalization, Hungary employs a growing number of foreign workers, prompting research into cross-cultural dynamics. Alshaabani & Rudnák (2023) examined international employees in Hungary, finding that trust in the workplace significantly boosts engagement, especially when combined with a positive conflict management climate (5). This suggests Hungarian firms that foster trust and handle conflicts constructively can better engage a multicultural team. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, perceived organizational support became critical. Alshaabani et al. (2021) reported that in Hungary, such support bolstered employees’ organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), especially when mediated by employee engagement (1). In practice, Hungarian employees who felt supported by their organization (through empathy, resources, and clear communication) were more likely to go above and beyond their formal duties, propelled by a sense of loyalty and emotional commitment.

Gender and generational nuances in Hungary also deserve attention. While the research directly comparing genders in Hungary is less prevalent than in broader CEE studies, we can infer patterns. Hungarian women might resonate with findings from surrounding countries: for example, women often value workplace atmosphere and teamwork slightly more than men. Generation-wise, younger Hungarians (Gen Z) likely share traits identified in Slovak research: they seek recognition, purposeful work, and work-life balance. An HR manager in Budapest may notice that Gen Z interns crave feedback and growth opportunities, while older generations might emphasize job security and stable benefits.

Moving north to Slovakia, motivation takes on a more financial flavor. Studies consistently show Slovak employees prioritize pay and tangible rewards as top motivators. In the Hitka et al. comparison, Slovak respondents rated financial factors (notably base salary) as their number-one motivator (2). Fringe benefits also ranked highly among Slovaks, underscoring the weight of extrinsic rewards. However, this doesn’t mean Slovak employees are solely money-minded. Interpersonal relations and job security still matter a great deal (both groups rated social needs the least important, but that’s relative to other factors).

Interestingly, while Hungarian employers were advised to emphasize career aspiration motivators, Slovak employers were urged to focus on mutual relationships too. This is a crucial takeaway for HR: even in a financially driven workforce like Slovakia’s, neglecting teamwork, recognition, and a positive climate would be a mistake. Dominika Vlacsekova and Ladislav Mura’s 2017 research on Slovak SMEs adds depth here (9). They found motivation is highly individual in small firms, with intrinsic factors (like achievement, personal growth) often outweighing extrinsic ones. In other words, Slovak employees in smaller enterprises may value meaningful work and autonomy, but they won’t say no to fair pay. Managers in Slovakia thus walk a tightrope: they must ensure competitive salaries, yet also foster a motivating environment with recognition and growth, especially to retain talent in a market where Western EU opportunities beckon.

Gender differences in Slovakia are pronounced in certain areas. One study spanning 4,444 Slovaks and 2,312 Czechs revealed that in Slovakia, basic salary was a motivation factor especially important for women (7). This might reflect historical pay equity issues or differing expectations; a savvy HR could use this insight to review compensation fairness. Additionally, women’s needs were found “more exacting” than men’s in general. They might expect a broader set of motivators to be satisfied (good boss, team, flexibility, etc.), whereas men might zero in on a few key items. For HR professionals, tailoring motivation programs with a gender lens – such as mentorship for women’s career advancement or ensuring transparency in evaluations – could yield dividends in engagement.

When it comes to generations, Slovak research by Fratričová & Kirchmayer (2018) highlights Gen Z’s desire for recognition and meaningful roles, but also points out barriers like “lack of feedback” dampening their motivation (11). A likely parallel in Hungary, and possibly the Czech Republic and Austria, is that younger employees want to feel valued and see impact quickly. HR programs such as early career achievement awards or cross-training could help motivate this cohort across the region.

The Czech Republic presents a complex motivation landscape that varies not only by gender but notably by job position and industry. A cutting-edge 2021 study by Ližbetinová et al. in the Czech transport and logistics sector demonstrated that “motivational preferences within job positions are different” (10). Managers, administrative staff, and front-line (performance) workers all showed distinct motivation profiles.

What motivates Czech managers? According to the study, managers placed highest importance on relational factors – having a good team was the #1 motivator for managers (score 4.51/5), even above salary. They also valued workplace atmosphere and a supportive supervisor’s attitude strongly. This suggests Czech managers thrive in environments where collaboration and positive culture are emphasized, perhaps because their financial needs are already met at higher pay grades.

For Czech administrative staff (e.g., office workers), the picture is mixed: salary was second only to team spirit, followed by atmosphere and fair evaluations. They’re a bridge between managerial and front-line attitudes—wanting good pay and good workplace relationships.

Front-line Czech workers (performance staff), much like their Slovak peers, rated base salary as the most important motivator (4.48/5), closely followed by job security and a good team. We see a recurring theme: at the ground level, financial security and stable working conditions are paramount, but a friendly team and trust in leadership (fair evaluation, good supervisor) rank high too.

What’s fascinating is how similar and how different these preferences are across the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia:

A “good work team” emerges as universally important. Hungarian and Czech employees (across many roles) cite it among top factors, and even Slovaks consider it significant (though slightly behind pay in importance).

Salary is a universal motivator but with varying rank: It’s #1 for Slovaks and Czech front-liners, #2 for many Czechs, and high but not top for Hungarians.

Job security is explicitly noted by Czech front-liners (likely also important in Hungary and Slovakia, given economic histories).

Career advancement & personal growth appear more in Hungary and among Czech managers (career factors had “higher preferences of managerial staff”), whereas they are less discussed in Slovakia’s top factors unless tied to generational aspirations.

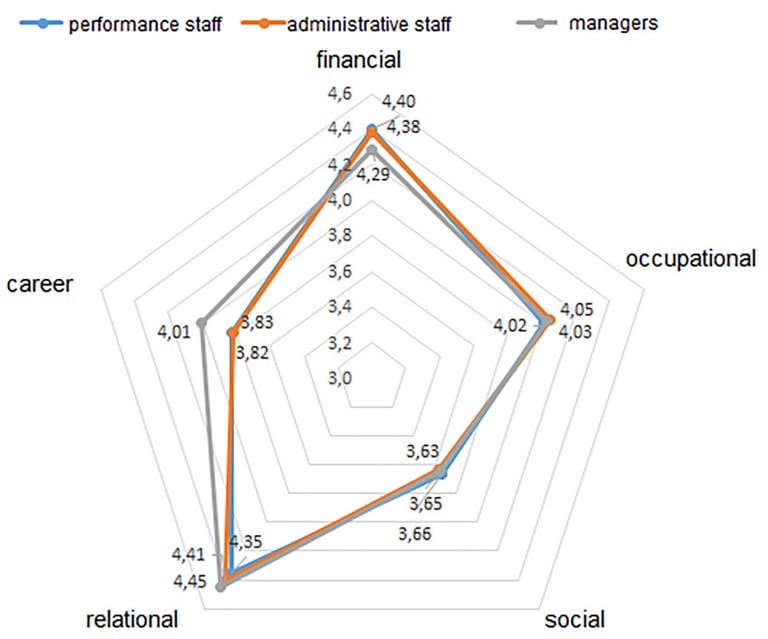

Visualizing these differences can be powerful. For instance, Figure 1 from Ližbetinová et al. (2021) provides a radar chart of motivator group preferences by job level in the Czech sample.

In it, one can see that:

Managers’ radar plot spikes on career and relational factors, dips on financial factors.

Performance (front-line) staff spike on financial and security factors, with lower emphasis on career.

Administrative staff fall in between, balanced across categories.

For HR professionals, the Czech findings hammer home that motivation programs must be segmented. A one-size-fits-all strategy will misfire. Instead:

For managers: Emphasize leadership development, team-building initiatives, and empowerment. They’re motivated by making an impact with their team and advancing strategically.

For white-collar/admin employees: Offer fair pay and recognition in tandem. They want competitive salary and a positive culture; consider balanced scorecard incentives that reward team performance and individual contributions equally.

For blue-collar workers: Job security, steady raises, and a collegial team may keep them committed. Retention bonuses or “safe workplace” awards could tap into their priorities.

Additionally, Czech research contributes to the gender discussion. The Sustainability study by Lorincová et al. (2019) (which included Slovak data) found white-collar women rated all motivators higher than men did, and women valued work atmosphere more (8). If we extrapolate to Czech or Hungarian contexts, HR should ensure workplace respect and atmosphere are upheld – a factor that can especially retain talented women and younger employees. Also, the study noted no gender difference in motivators for managers and blue-collar roles, hinting that at the extremes of organizational hierarchy, motivations converge regardless of gender (perhaps because basic needs or higher-order satisfiers become more uniform within those cohorts).

Austria, often perceived as more affluent and Western-oriented than its Central/Eastern European neighbors, presents an interesting baseline. You might expect Austrian employees, enjoying higher average incomes, to have very different motivators. Yet, a 2015 comparative study by Balážová found that the motivation level of service-sector employees in Slovakia and Austria was “very similar” (6). This was despite economic differences between the countries. The research sampled employees in comparable hotels in mountainous regions of both countries to control for industry and regional factors. Key motivators like applying one’s abilities, recognition, and basic salary showed no drastic variance in importance between Austrian and Slovak staff.

However, some significant differences in specific motivation factors did emerge:

Austrians might have placed higher importance on factors like prestige or mission of the company, reflecting perhaps a more individualistic or self-actualizing angle (as the abstract hints at prestige, self-actualization being among factors tested).

Slovaks rated basic salary very high, but if Austrians gave it slightly less emphasis, it could be due to higher baseline pay satisfying that need, allowing other factors to surface.

Nonetheless, the convergence in overall motivation level suggests a human universality: regardless of Austria’s economic edge, hotel employees in both countries wanted purpose, progress, and appreciation in their jobs. For HR practitioners in multinational contexts, this is heartening: many motivational programs can cross borders. If you design a scheme to motivate service staff in Bratislava, it may work in Salzburg too – just be mindful to tweak the emphasis. For example, an Austrian hotel might already pay well, so motivation could focus on career development and recognition, whereas a Slovak hotel might need to ensure pay is competitive and offer growth opportunities.

Generationally, Austria faces the same influx of Gen Z into the workforce. This cohort, as studies suggest, prizes diversity, continuous learning, and work-life balance – likely even more in a high living-standard country like Austria. Austrian companies, known for strong apprenticeship programs and social partnerships, may integrate Gen Z values by providing clear career pathways and well-being programs that the younger workforce expects.

To crystallize these findings, we present a comparative snapshot of motivational profiles in the four countries, highlighting both common threads and unique patterns.

Shared Top Motivators (Common Themes):

Competitive Base Salary: Universally important, though most critical in Slovakia and for Czech frontline workers (source). Even where not #1, it’s within the top 3 for virtually all groups studied. Implication: Always ensure fair, competitive pay as a foundation.

Good Work Team & Atmosphere: Emphasized strongly in Hungary (ranked highest) and Czech managers (highest), also valued in Slovakia and Austria. People want respectful, friendly workplaces. Implication: Invest in team-building, supportive leadership training, and conflict resolution (as trust and conflict climate matter in Hungary).

Job Security: Not explicitly measured in every study, but Czechs (4.41 for frontline) and likely Hungarians and Slovaks given regional history find it important. Implication: Communicate stability, provide clear career trajectories, even in uncertain times.

Recognition & Fair Evaluation: These appear in multiple studies – Hungarian and Slovak workers both care about recognition for good work. Czech administrative staff valued fair evaluation (4.42) nearly as high as salary. Implication: Implement transparent appraisal systems and frequent positive feedback loops (particularly crucial for Gen Z across all countries).

Key Differences (Unique Nuances):

Interpersonal vs. Financial Emphasis: Hungary leads on interpersonal motivation (relationships first), whereas Slovakia leads on financial motivation (money first) (source). The Czech Republic straddles these: employees’ emphasis shifts by role (managers more interpersonal, workers more financial). Austria aligns closer to Slovakia in service-sector focus but with slightly less disparity.

Gender Gaps: While not deeply studied for Austria, in Czech/Slovak contexts, women expect more from their job environment (especially white-collar roles: e.g., women gave higher importance ratings to all motivators than men). Slovak women zero in on pay equity (base salary importance)】. Hungarian data implies women may similarly value social aspects strongly (as they did in the Slovak/Hungarian comparison for some factors).

Generational Shifts: All four countries face Gen Z and Millennial employees who diverge from older colleagues. Gen Z tends to demand more feedback, meaning, and flexibility, as noted in regional research. Traditional motivators like “mission of the company” or “prestige” might mean more to younger Austrians/Czechs in knowledge sectors, whereas older generations may stick to pay and stability. For HR, generational mix in teams means offering a blend of motivators – perhaps innovative projects and upskilling for the young, and recognition of loyalty and secure benefits for the seasoned staff.

Visual Comparison:

Below is a summary table contrasting Hungarian employees’ top motivators against those from Slovakia, Czech Republic, and Austria, drawing on the literature:

Motivation Factor

Base Salary

Good Team /

Co-workers

Work Atmosphere

Career Advancement

Recognition / Appreciation

Job Security

Fringe Benefits

Intrinsic Meaning

Hungary (general)

High (top 3, but not #1)

Very High (#1)

High (correlated with team)

High (especially younger gen)

High (Hungarians value it)

High (implied)

Moderate (not top 3)

Increasing (esp. young)

Slovakia (general)

Very High (#1 overall)

High (top 5)

Moderate (mid-tier)

Moderate (not top overall)

High (Slovaks value it too)

High (implied)

High (top financial after salary)

Growing (Gen Z cares here)

Czech Republic (varies by role)

Mixed: #1 for blue-collar; lower for managers

Very High (#1 for managers/admin)

High (admin staff ~4.43)

High for managers (part of “career factors”)

High (fair evaluation key for Czechs)

High (#2 for front-line Czechs)

Moderate (mentioned, but not top for Czechs)

Not highlighted in study but present (e.g., “mission” factor)

Austria (service sector)

High (important, but not sole focus)

High (especially in hospitality teams)

Likely high (customer service context)

Moderate (depends on org structure)

High (universal desire)

Moderate-High (Austrians more secure generally)

Moderate (expected in Austria)

Increasing (younger workforce)

Sources: Hitka et al. 2017; Balážová 2015; Lorincová et al. 2019; Ližbetinová et al. 2021.

This comparative view confirms that while money talks everywhere, culture and context modulate its voice. Hungary’s motivational melody plays in a more people-centric key, Slovakia’s in a material minor, the Czech Republic’s in a harmonic blend by job role, and Austria’s in a balanced, perhaps slightly self-actualized tone.

Motivating employees is both an art and a science—one that must be attuned to local culture and individual differences. The studies reviewed provide actionable insights for HR professionals operating in Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Austria:

Tailor Motivation Programs by Country and Culture: A strategy that resonates in Budapest (emphasizing team cohesion and meaningful work) might need tweaking in Bratislava (highlighting pay and rewards). Recognize these cultural priorities when designing incentive schemes or corporate values. For example, Hungarian firms might invest more in team-building retreats, whereas Slovak firms might prioritize bonus structures – but neither should ignore the other aspect.

Account for Demographics – Gender & Generation: In developing engagement plans, consider if your workforce skews in ways that research flags as significant. If you have many female white-collar employees in Prague or Bratislava, ensure your HR policies address their expectations (e.g., fairness, work-life balance, salary equity). If onboarding Gen Z hires in Vienna or Debrecen, implement mentorship, rapid feedback, and a sense of purpose to tap their motivation. Small gestures like recognition in company newsletters or Q&A sessions with leadership can satisfy the Gen Z need for belonging and significance.

Leverage Universal Drivers – The “No-Regret” Moves: Some motivators are safe bets across all four contexts. Fair pay, respectful treatment, recognition, and growth opportunities form a universal foundation. No employee ever complains that their hard work was appreciated too much or their career stagnation was addressed too quickly. Build these into your HR DNA – regular performance reviews with constructive feedback, clear promotion pathways, team recognition events, etc.

Monitor Engagement Metrics and Solicit Feedback: Use surveys and stay interviews to gauge if your employees’ motivation aligns with these findings. Perhaps Hungarian staff confirm they love the company culture but feel salaries are a tad low, or Czech employees might say they value the new bonus system but also really want leadership training. Data-driven adjustments will refine the general research to your specific organization’s context.

Cross-Pollinate Best Practices: One perk of comparing countries is stealing like an artist. Austrian firms’ success in maintaining high motivation despite economic differences (as seen with similar motivation levels to Slovakia) might stem from their structured apprenticeships or social dialogue – ideas worth exploring in neighboring countries. Conversely, the Hungarian focus on meaningful work could inspire Austrian and Czech companies to deepen employees’ connection to organizational mission, not just their immediate job tasks.

In conclusion, understanding employee motivation across Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Austria reveals a rich tapestry of human needs. For HR professionals, the mandate is clear: be culturally aware but also look at the individual. Motivation is personal, yet trends guide us on where to look first.

A Hungarian might say, “I stay because my team feels like family,”

a Slovak, “I go where I’m paid what I’m worth,”

a Czech, “I excel when I’m trusted and supported,”

and an Austrian, “I engage when I see purpose and growth.”

By listening to these voices and integrating research-based insights, HR leaders can cultivate workplaces that transcend borders in motivational excellence.

Figure 1 - Motivational preferences by job type, source: Ližbetinová et al (2021)

Hungarian Employees: Motivated by Meaning and Mutuality

Slovakia: Financially Driven but Not One-Dimensional

Czech Republic: One Size Doesn’t Fit All (Job Levels Matter)

Austria: Similar Tune, Different Stage

Motivation Factor

Base Salary

Good Team /

Co-workers

Work Atmosphere

Career Advancement

Recognition / Appreciation

Job Security

Fringe Benefits

Intrinsic Meaning

Motivation Factor

Base Salary

Good Team /

Co-workers

Work Atmosphere

Career Advancement

Recognition / Appreciation

Job Security

Fringe Benefits

Intrinsic Meaning

Motivation Factor

Base Salary

Good Team /

Co-workers

Work Atmosphere

Career Advancement

Recognition / Appreciation

Job Security

Fringe Benefits

Intrinsic Meaning

Motivation Factor

Base Salary

Good Team /

Co-workers

Work Atmosphere

Career Advancement

Recognition / Appreciation

Job Security

Fringe Benefits

Intrinsic Meaning

Hungary (general)

High (top 3, but not #1)

Very High (#1)

High (correlated with team)

High (especially younger gen)

High (Hungarians value it)

High (implied)

Moderate (not top 3)

Increasing (esp. young)

Slovakia (general)

Very High (#1 overall)

High (top 5)

Moderate (mid-tier)

Moderate (not top overall)

High (Slovaks value it too)

High (implied)

High (top financial after salary)

Growing (Gen Z cares here)

Czech Republic (varies by role)

Mixed: #1 for blue-collar; lower for managers

Very High (#1 for managers/admin)

High (admin staff ~4.43)

High for managers (part of “career factors”)

High (fair evaluation key for Czechs)

High (#2 for front-line Czechs)

Moderate (mentioned, but not top for Czechs)

Not highlighted in study but present (e.g., “mission” factor)

Austria

(service sector)

High (important, but not sole focus)

High (especially in hospitality teams)

Likely high (customer service context)

Moderate (depends on org structure)

High (universal desire)

Moderate-High (Austrians more secure generally)

Moderate (expected in Austria)

Increasing (younger workforce)

Comparative Snapshot: Hungary vs. Slovakia, Czech Republic, Austria

Conclusion and HR Takeaways

Sources

Alshaabani, A., Naz, F., Magda, R., & Rudnák, I. (2021). Impact of Perceived Organizational Support on OCB in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic in Hungary: Employee Engagement and Affective Commitment as Mediators. Sustainability, 13(14), 7800. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/14/7800

Hitka, M., Lorincová, S., Ližbetinová, L., & Schmidtová, J. (2017). Motivation Preferences of Hungarian and Slovak Employees are Significantly Different. Periodica Polytechnica Social and Management Sciences, 25(2), 117-126. https://pp.bme.hu/so/article/view/10052

Csordás, G., Matuszka, B., Sallay, V., & Martos, T. (2022). Assessing meaningful work among Hungarian employees: testing psychometric properties of work and meaning inventory in employee subgroups. BMC Psychology, 10(56). https://bmcpsychology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40359-022-00749-0

Pirohov-Tóth, B. (2019). Role of Management in The Effect on Employee Motivation of Organizational Performance – Hungarian Case Study. Journal of Economics and Business, 2(2). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3413667

Alshaabani, A., & Rudnák, I. (2023). Impact of Trust on Employees’ Engagement: The Mediating Role of Conflict Management Climate. Periodica Polytechnica Social and Management Sciences, 31(2), 153–163. https://pp.bme.hu/so/article/view/18154

Balážová, Ž. (2015). Comparison of Motivation Level of Service Sector Employees in the Regions of Slovakia and Austria. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23, 348–355. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212567115003937/pdf

Balážová, Ž. (2017). Differences in Employee Motivation in Slovakia and Czech Republic. In Issues of Human Resource Management (pp. 97-109). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317422114_Differences_in_Employee_Motivation_in_Slovakia_and_Czech_Republic

Lorincová, S., et al. (2019). Employee Motivation as a Tool to Achieve Sustainability of Business Processes. Sustainability, 11(13), 3509. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/13/3509

Vlacsekova, D., & Mura, L. (2017). Effect of Motivational Tools on Employee Satisfaction in Small and Medium Enterprises. Oeconomia Copernicana, 8(1), 111-130. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316612735_Effect_of_motivational_tools_on_employee_satisfaction_in_small_and_medium_enterprises

Ližbetinová, L., Hitka, M., Soušek, R., & Caha, Z. (2021). Motivational Preferences Within Job Positions Are Different: Empirical Study from the Czech Transport and Logistics Enterprises. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 34(1), 2387-2407. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1331677X.2020.1863831

Fratričová, Jana & Kirchmayer, Zuzana. (2018). Barriers to work motivation of Generation Z. XXI. 28-39. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329145147_Barriers_to_work_motivation_of_Generation_Z

Have you read our other articles? Go to Motioo Insights

Do you have any questions or comments? Contact us