Motivation in the World of Manufacturing – How to Keep the Workforce Energized in the Production Sector

Andras Rusznyak

6/11/202511 min read

Ha magyarul szeretnéd olvasni a cikket, kattints ide

Introduction

In the manufacturing sector, which employs around 15% of the EU workforce, maintaining employee motivation is a critical issue. The nature of work in factories is often different from that in other sectors, with routine tasks, physical demands and rigid work schedules (1). These circumstances pose challenges for HR professionals, as motivational dynamics are different from those in the service or IT sectors, for example. In this article, we review how motivation in manufacturing differs from that in other sectors, what tools have been shown to be effective or ineffective according to research, and the challenges of motivating blue-collar (physical) and white-collar (mental) workers together within an organisation.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

This article is intended to be an informative piece, based on various research papers and studies listed under the Sources section. These studies were conducted at different times and each had their own limitations. We did not carry out field research, surveys or interviews, nor did we validate the findings of the mentioned studies under current conditions.

We utilized generative AI in the making of this article.

Several European surveys show that the motivational landscape in manufacturing is different from that in many service sectors. According to a comprehensive analysis by Eurofound, in jobs that require routine machine production – typically factory-line jobs – employees have much lower levels of involvement in decisions and autonomy than in jobs that involve people or have a high technological content (2). Due to limited autonomy and monotonous tasks, factory workers often work in so-called ‘passive’ jobs, which, although low-pressure, can lead to frustration and loss of motivation due to their monotony. At the same time, ‘low-stress’ jobs, i.e. jobs that are both low-intensity and provide high autonomy (1), are rare in manufacturing, which are more common in other sectors (e.g. creative or knowledge-based areas) and are more conducive to motivation.

The physical working environment – noise, dangerous machinery, repetitive movements – makes it even harder to stay motivated. An EU report found that manufacturing industries have much higher than average levels of physical risks and work-related stress (1). Constant stress and physical fatigue can undermine employee motivation unless companies pay special attention to improving working conditions and work-life balance. It is no coincidence that a UK survey found that only 49% of manufacturing workers look forward to going to work, compared to other sectors where this rate is higher. However, the best manufacturing companies – where they consciously build a motivating work culture – have already increased this rate to 77% of their employees (3). All this shows that strong engagement can be created in manufacturing, but a different approach may be needed than in an office environment.

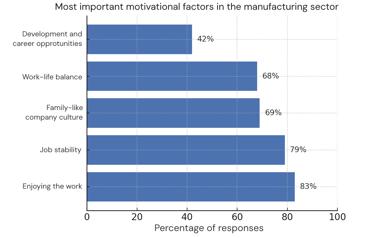

Several recent studies have looked at what motivates manufacturing workers and what HR tools work best in this sector. A 2021 study by the Manufacturing Institute found that the biggest reasons for employees to stay are enjoying their work and feeling safe at work – 83% and 79% of factory workers surveyed cited these as their main reasons for staying. A supportive, family-like culture (69%) and a good work-life balance (68%) were also cited as important motivators. In contrast, training and career opportunities were cited by relatively fewer workers (42%) as reasons for staying – although these were already highly important for motivation for two-thirds of younger workers under the age of 25 (5). This is illustrated in the figure below.

The results above suggest that, in addition to financial benefits and a sense of security, the enjoyment of work and a positive organizational culture are also key in the manufacturing industry. The latter includes caring about the well-being of employees. The analysis by Great Place to Work UK highlights that the most successful manufacturing companies have comprehensive well-being programs to help employees – whether they work in a factory or an office – maintain their physical and mental health. An example of this is the 24/7 online wellness platform introduced by a British manufacturing company, which is available to all employees, so that anyone from truck drivers to machine operators can benefit from content and training that supports mental, physical or financial well-being (3). Such initiatives have been proven to increase commitment: where employees feel that the company cares about their well-being, they are much more willing to come to work and are less likely to switch.

Management attitude is also a key factor. The traditionally hierarchical world of manufacturing has long placed little emphasis on humane leadership, yet recent data suggests that empathetic, supportive leaders can dramatically increase employee motivation. According to Great Place to Work, employees who feel their management truly cares about them are seven times more likely to recommend their company as a “great place to work” than those whose bosses don’t care about them as a person. This same caring also impacts employee health and loyalty: employees who feel their managers care about them find the company a healthier, more balanced place to work and plan to stay there for the long term. It’s no coincidence that in the best-performing manufacturing companies, employees themselves often cite good bosses as the most attractive thing about their workplace (3). Personal attention, recognition and fair treatment are therefore essential motivational tools: an American survey revealed that almost all employees who feel valued by their company are highly motivated (97%) and satisfied with their work, while only half of those who do not feel valued are motivated. In fact, the former are more than four times more likely to report a high level of commitment than the latter (59% vs. 13%). In contrast, unrecognized employees are much more often stressed and ten times more likely to change jobs (5). The lack of recognition is therefore a typical example of ineffective motivational practice – the lack of praise, appreciation and fair treatment has a demoralizing effect and increases turnover.

We can also find proven solutions to the challenges of physical and monotonous work. Monotonous, repetitive tasks almost certainly reduce motivation and performance in the long run. According to a case study in an Italian factory, “performing the same task over and over again not only demotivates the operator, but also increases the likelihood of making mistakes” – quoting one worker who said that after 10 months of doing the same operation, he lost motivation and made mistakes more often (6). One of the most effective countermeasures is job rotation and multiskilling, i.e. allowing workers to try out different tasks. According to research by Eurofound, “autonomous multiskilling” – when workers can rotate different tasks independently – is associated with higher motivation and better company performance (1). Experiences in Italy confirm this: workers are highly motivated to break the monotony of work, learn new things in the production process and reduce one-sided workload. In factories that use rotation, workers report less physical and mental fatigue, which increases their motivation and attention (6). More varied work, the opportunity to learn and the feeling of development are strong intrinsic motivators – as opposed to monotony, which can wear out even the most enthusiastic workforce.

The role of performance incentives should not be forgotten either. In the manufacturing industry, various financial incentives and performance bonuses (e.g. piece rates, quality bonuses) have traditionally been widespread as external motivational tools. With the spread of Industry 4.0 technologies, this trend is further strengthened: a recent Swiss survey showed that companies that introduce digital technologies use performance-based pay much more often than their technology-averse counterparts. Digitalization enables more accurate measurement and tracking of employee performance, so companies tend to motivate employees with more bonuses linked to targets to take advantage of the control provided by the new measurement data. This phenomenon was observed at both the management and subordinate levels in the Swiss companies studied (4). However, the effectiveness of financial incentives is a double-edged sword: when used properly, they can increase productivity and focus, but if they are perceived as excessive pressure by employees, they can damage morale. According to the literature, money alone is rarely enough to ensure long-term commitment, especially among the younger generation – which is why it is important to complement extrinsic rewards with measures that strengthen intrinsic motivation (interesting work, recognition, involvement in decisions, etc.). In addition, transparency and fairness in performance evvaluation are key: if employees feel that the distribution of bonuses is unfair, it can become demotivating. Overall, research suggests that well-designed financial incentives in manufacturing are useful elements of the motivational toolbox – but they are not a substitute for a good atmosphere, development opportunities and attentive management.

In manufacturing companies, blue-collar (physical) and white-collar (mental or managerial) workers often work together, and their motivation presents different challenges. The two groups often have different experiences and expectations at work. The daily routine of production workers is typically defined by shifts aligned with machines, repetitive tasks, and strict quality and safety standards. In contrast, office or engineering staff enjoy more autonomy, can allocate their time more flexibly, and their work often involves creativity or strategic decision-making. It is not surprising that white-collar workers tend to feel more motivated and recognized than production line workers if the company does not consciously pay attention to this divide.

A survey of US manufacturing workers highlighted these differences. The survey found that senior managers almost unanimously felt they had a say in decisions (96% of managers were satisfied with their decision-making authority), while only 67% of frontline workers felt they had a meaningful influence on decisions affecting their work. Similar gaps were also found in the extent to which they perceived internal career opportunities to be ensured (85% of managers said they had career prospects, compared to 70% of manual workers) and in their satisfaction with training and development opportunities (managers: 94%, manual workers: 66%) (5). The figure below summarises these differences.

The above differences pose a serious challenge for HR: if manual workers consistently feel like they are “second-class” employees within the organization, it will damage their morale and performance, and can easily lead to dissatisfaction or even strikes and turnover. The key to the solution is to bridge the gap between the two groups, creating a common corporate culture and values. In practice, this means that the company must address and involve all employees, regardless of whether they work in an office or a factory. Research by Great Place to Work highlighted that the best workplaces “make every employee feel equally important, regardless of position” and give everyone the opportunity to express their opinions and share their ideas (3). This kind of inclusive approach reduces the distance between company management and manual workers.

It is also important that blue-collar workers see their own development and advancement prospects within the company. It is a common mistake for production workers to not have a clear career path (e.g., team leader, shift leader, or expert), so they may feel that they have “no future” within the organization. However, when front-line workers also have influence and advancement opportunities, their satisfaction and loyalty approach those of those in management positions. For example, in the aforementioned survey, manual workers who were able to participate in decision-making showed much less of a lag in terms of promotion and training satisfaction – about two-thirds of the initial differences disappeared (5). This clearly shows that improving involvement and communication has a positive impact on the motivation of the entire organization.

Of course, there may be practical differences in motivating the two groups. What works for office workers – for example, a flexible home office or an inspiring meeting culture – may not be applicable on the production line. Therefore, HR needs to develop tailored motivation programs. For blue-collar workers, appropriate pay, job security and working time arrangements (e.g. fair shift schedules, overtime compensation) as well as improving the physical environment at work are particularly important. In contrast, white-collar workers often prioritize professional challenges, career prospects, company values and intellectual recognition. Yet, the secret to success is to find a common denominator: ultimately, every employee wants to be appreciated, have influence over their own work, develop and work in a fair, supportive environment. If a company is able to enforce these principles throughout the organization, it can motivate both blue-collar and white-collar employees. In the era of Industry 4.0, the involvement of both groups is essential: the successful implementation of technological changes also depends on whether manual workers feel trained and treated as partners, or whether they fear for their jobs due to automation. Experience shows that if management pays attention and engages in dialogue with employees, digitalization can also be a source of motivation (learning new skills, more interesting work processes) instead of only causing anxiety.

Maintaining and increasing the motivation of manufacturing workers is now a strategic task in Europe. Due to the specificities of the sector – physical strain, rigid work organization, safety requirements – it requires a different approach than some other industries, but research shows that with the right measures, outstanding commitment and satisfaction can be achieved in factories. This requires a combination of proven extrinsic and intrinsic motivational tools: competitive wages and a sense of stable employment are essential, but not sufficient on their own. The smart use of performance incentives is equally important, but only if they are applied fairly and transparently and do not come at the expense of human aspects. The real competitive advantage is created when we also win the hearts of employees– that is, when employees find their work meaningful and enjoyable, see the opportunity for development and feel valued. The importance of organizational culture is crucial here: in a supportive culture built on communication and involvement, people cope better even in the most difficult circumstances.

The joint motivation of blue-collar and white-collar workers deserves special attention. The modern HR approach breaks down walls: it consciously provides forums and programs where everyone can voice their opinions, and it develops mechanisms (such as recommendation systems, joint team buildings, internal communication platforms) that strengthen cohesion. If the manual worker feels that his opinion matters in the same way as the office engineer, and both receive similar recognition for their performance in their own field, then they will feel part of a common, motivated team. Ultimately, this is reflected not only in the well-being of the workers, but also in productivity, quality and innovation – since an engaged workforce is less prone to errors (6), more open to innovations and more loyal to the company.

In summary: maintaining motivation in the manufacturing industry is a challenge, but it is far from impossible. The secret to success is to combine a people-centric approach with industry-specific strategies. Recent European and international research unanimously tells HR professionals to pay attention to employee engagement, recognition and development, because these tools have the same – if not greater – impact on employee motivation within the factory walls than anywhere else.

The unique nature of motivation in manufacturing compared to other sectors

Effective and ineffective motivational tools according to research

Motivating blue-collar and white-collar workers in the same organization

Summary

Figure 2: Data from a 2020 survey shows that senior managers in manufacturing are significantly more satisfied with their involvement in decision-making, internal career opportunities, and training opportunities than frontline (physical) workers (5). This illustrates the different experiences of white-collar and blue-collar workers.

Figure 1: According to a survey by the Manufacturing Institute (2021), enjoyable work, job security, and a supportive, family-like organizational culture are the most important motivating factors among manufacturing workers, while training and career opportunities were highlighted less overall – although the latter plays a much greater role among younger workers (5).

Sources

Eurofound – Manufacturing: Working Conditions and Job Quality (2015). Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/system/files/2015-02/ef1384en26.pdfEurofound – Work Organisation and Employee Involvement in Europe (2013). Eurofound Research Report.

https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/system/files/2014-12/ef1330en.pdfGreat Place to Work UK – 3 Ways Manufacturing & Production Organisations are Driving Employee Engagement (Beth Taylor, 26 March 2024)

https://www.greatplacetowork.co.uk/resources/3-ways-manufacturing-production-organisations-are-driving-employee-engagementLehmann, J. & Beckmann, M. – Digital technologies and performance incentives: evidence from businesses in the Swiss economy (Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics, 2025).

https://sjes.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41937-024-00132-3The Manufacturing Institute & American Psychological Association – Manufacturing Engagement and Retention Study (2021).

https://www.themanufacturinginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/APA-Study_final.pdfCirillo, V., Rinaldini, M., Staccioli, J., Virgillito, M.E. – Workers’ awareness context in Italian 4.0 factories (LEM Working Paper, 2018; arXiv preprint).

https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/203066/1/1024898326.pdf

Have you read our other articles? Go to Motioo Insights

Do you have any questions or comments? Contact us